The idea of considering students’ emotions in context of online or blended learning may seem absurd. There are numerous factors instructors consider when teaching online that would seem to take priority over students’ emotional state. Yet a recently published paper “Measuring and Understanding Learner Emotions: Evidence and Prospects” reveals that feelings of learners—their emotions can impact learning in online and blended environments, specifically motivation, self-regulation and academic achievement (Rienties & Rivers, 2014). I share with readers in this post the concept of ’emotional presence’, what it means for instructors teaching online, and how instructors can address learners’ emotions in their online courses.

The idea of considering students’ emotions in context of online or blended learning may seem absurd. There are numerous factors instructors consider when teaching online that would seem to take priority over students’ emotional state. Yet a recently published paper “Measuring and Understanding Learner Emotions: Evidence and Prospects” reveals that feelings of learners—their emotions can impact learning in online and blended environments, specifically motivation, self-regulation and academic achievement (Rienties & Rivers, 2014). I share with readers in this post the concept of ’emotional presence’, what it means for instructors teaching online, and how instructors can address learners’ emotions in their online courses.

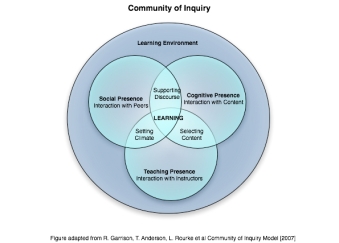

The idea of emotional presence builds on the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model. The model provides educators and course designers with a framework to address factors unique to learning online within three dimensions: 1) social presence: where students project their personal characteristics within the online community that position them as ‘real’ people, 2) teaching presence: where the instructor directs the learning process such that students’ sense he or she is ‘there’, and 3) cognitive presence where learners construct meaning through sustained dialogue and communication. Developed by Garrison, Anderson and Archer, the CoI model continues to evolve and is the subject of several empirical studies (The Community of Inquiry, n.d.) The three dimensions are the focus of the framework, but the idea of learner emotions and the role they play in the online environment is not addressed. Until now. Recent papers and articles address how learners feelings impact their learning online.

Emotional Presence Defined

Emotional presence may still seem far-fetched. I like how Terry Anderson, one of the founders of the CoI model describes in a recent blog post how he responded when asked why emotions weren’t included in the original model: “The COI model was developed by 3 men from southern Alberta (Canada’s cowboy country) and that REAL men in our limited world didn’t do emotions! (2014). But Anderson is supportive of emotional presence as a concept, and of his colleague Maria Cleveland-Innes who published a paper with P. Campbell “Emotional Presence, Learning and the Online Learning Environment (2012). In the paper the authors describe emotional presence as underpinning the broader online experience (pg. 8). They define emotional presence as:

Emotional Presence is the outward expression of emotion, affect, and feeling by individuals and among individuals in a community of inquiry, as they relate to and interact with the learning technology, course content, students, and the instructor.

Rienties and Rivers added the emotional circle to the original Venn diagram of Garrison, Anderson and Archer (2000)

Why Bother with Emotions?

One might wonder why even bother considering how students are feeling. More so in online environment where it seems impossible to address. Yet after reviewing the research there is evidence from a variety of sources that suggests emotions play a powerful role in learners’ engagement and achievement, and that the role of emotions in online learning deserves special consideration (Artino, 2012; Rienties & Rivers, 2014).

How to Build Emotional Presence in an Online Course

In face-to-face (F2F) classes emotional presence happens seamlessly. Teachers detect emotional cues of students due to their physical proximity. I found several studies examining presence behaviors of teachers working with students in the classroom—a phenomenon labeled ‘instructor immediacy‘. Though it’s beyond the scope of the post to go deeper, several studies validate the importance of such cues and the role of emotions in facilitating learning (Andersen, 1979). If we apply these principles to learning environments without physical closeness, in an online course for instance, there needs to be a deliberate effort to include cues that support emotional presence. Cues visible in F2F settings include, smiling, making eye contact, knowing students by name, and demonstrating interest. In online classes, it’s easier-said-than-done.

The technology and physical distance create a barrier that make is difficult for instructors to read and reach their students. There is no consensus in the research on best practices for addressing emotional presence in online classes effectively. But between the papers there are several suggestions which I summarized below.

-

The Vibe’ wellbeing word cloud from the University of New England, 2012, (Rienties & Alders, pg. 12)

Synchronous discussions via chats or video conferences provide instructors opportunity to assess and read learners emotions that may impact their learning progress, such as uncertainty, confusion, even positive emotions, interest and enthusiasm.

- Wordclouds implemented in Australian Universities display dynamic pictures of students emotions collectively (see image). It serves several purposes: gives the instructor insight into how students are feeling, and validates students feelings by sharing. Useful for certain phases within a course: the beginning when students might be apprehensive, or during a difficult module or week.

- Analyzing written text and online discourse in discussion forums by looking for key words may provide insight into learners emotions. Such words as I feel “frustrated”, “overwhelmed”, “behind” are a few examples.

- Examining learners’ online behaviour in terms of the frequency of logging on, clicks and time spent on certain pages within the LMS (caution, this method provides a one-dimensional perspective and may only be useful when considering other factors).

Conclusion

As online learning evolves and allows us to bring quality education to the learner, there are barriers to consider and overcome. Reading student cues and considering their feelings that may affect their progress is one area that we cannot ignore. It’s studies like those mentioned here that brings us closer to delivering personal, quality and meaningful learning to students.

References

- Andersen, J.F. (1979). Teacher immediacy as a predictor of teaching effectiveness. In D. Nimmo (Ed.), Communication Yearbook, 3 (pp.543-559). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

- Anderson, T. (2014, December 16). New report on emotional presence in online education [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://terrya.edublogs.org/2014/12/16/new-report-on-emotional-presence-in-online-education/

- Artino, Anthony R. (2012). “Emotions in online learning environments: Introduction to the special issue.” The Internet and Higher Education 15(3): (pp. 137-140).

- Cleveland-Innes, M., & Campbell, P. (2012). Emotional presence, learning, and the online learning environment. The International Review Of Research In Open And Distributed Learning, 13(4), 269-292. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1234

- Immediacy in the Classroom. (n.d.). Carleton College. Retrieved from http://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/affective/immediacy.html

- Rientes, B. R., & Rivers, B. A. (2014). Measuring and understanding learner emotions: Evidence and prospects (Review 1, pp. 1-16, Rep.). Learning Analytics Community Exchange.

How will online courses for credit at traditional tuition rates be able to compete in 2013?

How will online courses for credit at traditional tuition rates be able to compete in 2013? 3. Build in Collaborative Group Work:

3. Build in Collaborative Group Work: