I share here a five-step strategy for integrating technology tools to support meaningful learning in online courses. However I’d be misleading readers if I suggested that effective technology integration is as easy as following a five-step formula; I’m likely not sharing anything new with readers by emphasizing it’s not. A key component when creating effective online learning experiences with ed-tech tools that lead to collaborative learning (and not busy-work that students abhor), is determining why and how.

The why and how needs to be determined well before implementing the five steps. I was inspired to delve into the strategy behind ed-tech integration after reading “10+ No-Signup Collaboration Tools You Can Use in 10 Seconds” (Couch, 2015). I tweeted the article last week (below). It got several views and likes which is not surprising since most online instructors are looking to incorporate interactivity into their courses, and the tools featured were free and easy to use. Yet despite my enthusiasm for the tools, I felt the need to share a strategy for integrating tools effectively. The tools are alluring—as the article’s headline suggests the collaborative tools ‘can be used in 10 seconds’. Yet each tool on its own is neutral, zero-sum; there’s no value-added when using technology for student learning unless integrated with a purposeful strategy, and an approach that’s grounded in the why and how.

The why and how needs to be determined well before implementing the five steps. I was inspired to delve into the strategy behind ed-tech integration after reading “10+ No-Signup Collaboration Tools You Can Use in 10 Seconds” (Couch, 2015). I tweeted the article last week (below). It got several views and likes which is not surprising since most online instructors are looking to incorporate interactivity into their courses, and the tools featured were free and easy to use. Yet despite my enthusiasm for the tools, I felt the need to share a strategy for integrating tools effectively. The tools are alluring—as the article’s headline suggests the collaborative tools ‘can be used in 10 seconds’. Yet each tool on its own is neutral, zero-sum; there’s no value-added when using technology for student learning unless integrated with a purposeful strategy, and an approach that’s grounded in the why and how.

The Approach

The Approach

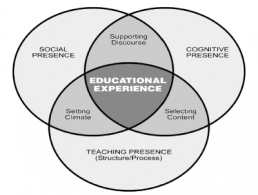

Approaching technology integration as a multi-dimensional, strategic exercise is not the usual approach by course designers and instructors, yet is essential to creating conditions for learning. Though it sounds obvious, the first phase is exploring what, why and how. This phase determines if the tool ‘makes sense’—sense within the context of the course learning objectives, and the sense it makes to students. Both are at the core of every effective education technology strategy, yet in my work experience I’ve found that integrating tech tools into learning activities is one of the most neglected areas of course design even though it has significant impact on student learning.

WHAT and WHY

Teachers and faculty need to know why they are using the tool, which begins with what—what learning goal or objective does using a learning activity support? What kind of learning activity, e.g collaborative group project, discussing forum posting, group case study analysis, will support student learning that will lead to meeting the objective? What tool can potentially support the activity? Next is why —why would or should I use the tech tool? Why this tool over another? It seems so simple to ask ‘why’, yet the answers can often be complex; all the more reason to begin with why.

But finding answers to the why for educators is not enough—students need to know the why—why are they doing this activity? The latter is often missed. Educating students about the purpose of a learning activity is an essential element that supports pedagogically sound teaching, where a tool is used not for the sake of using a tech tool, but used purposefully. Otherwise it’s becomes a busy-work assignment—using a ‘cool’ tool. So how do we let students know the why? We tell them. This means when writing a brief description of a learning activity for students to include within the course site that includes a sentence that begins with “The purpose of this activity is to….” . The activity purpose should align with one of more of the course learning objectives. Articulating the purpose makes clear that the activity is worthy of students’ time and commitment; student motivation is far higher when they know the purpose and premise.

HOW

When approaching the how, educators should consider a tool from two perspectives: 1) the technical aspects of the tool—how it works, what it does, how feasible it is to use the tool within a course, e.g. whether students will be able to access the tool easily, the learning curve for using the tool, and 2) the pedagogical aspects—how the tool will support learning and how it’s use will be described to students so that it’s becomes seamless experience so the focus is on learning and not the technology. Which is why as mentioned, there are several considerations, layers of complexity to integrating tech tools. The five-step strategy (below) addresses most of the factors that need consideration when integration educational technology, while the first phase of examining why, why and how addresses the remaining.

Five-Step Strategy for Tech Integration

- Consider: Will this application/tool enhance, improve instruction or motivate learners? What similar applications/tools are there to consider? I

- Review the learning objectives for the course or lesson to determine what activity (with support of the tool ) will support learning. Which tool might best support meeting objective?

- Identify the content/concepts students need to learn – review, augment and/or update content that students may need to access during activity

- Assess the ed-tech application/tools – will it encourage students to apply the content and learn the material, construct knowledge and promote critical thinking?

- Select and implement the best application. Create concise instructions of how-to use tool. Allow time for learning of tool and learning of course content

The HOW for Students

I would like to highlight for readers Step 5—the last component of step five that addresses the student—how are students going to use the tool and how will it be explained to them?. This component including in the course concise instructions for the activity and the use of the tool, is critical yet often overlooked. Students need to know why they are doing a collaborative activity, then how they are going to go about it, what tool they will use so that they can get down to business of learning. Otherwise their time is spent of figuring out what they are doing and why they are doing it. Wasted time.

Closing

There are so many tremendous educational technology tools and applications available now, more than ever before, but unless they are integrated effectively and thoughtfully, it’s a zero-sum game—zero learning and a waste of resources.

Collaborative Tools

- Microsoft Unveils Collaboration Features and 35 Partners for Office for Education, Edsurge

- 10+ no-signup collaboration tools you can use in 10 seconds, Makeuseof

- 20 Fun Free Tools for Interactive Classroom Collaboration, Emerging EdTech

References

- Couch, A. (2015, March 5). 10+ no-signup collaboration tools you can use in 10 seconds. Retrieved from http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/10-no-signup-collaboration-tools-can-use-10-seconds/

- Morrison, D. (2012, June 22). How to choose the best ed-tech tools for online instruction [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://wp.me/p1N30w-QL

- OnlinelearningI. (2016, June, 22). Good tools here; Padlet one of my favorites. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/onlinelearningI/status/745696408016035840

- Padlet. Retrieved from https://padlet.com/