I recently listened to a lecture ‘The importance of place’ from a Great Courses series on Cultural and Human Geography. The professor discussed the process of ‘place-making’ that occurs when humans interact with, and modify a physical space to make it their own. The result is a distinctive place with a unique culture shaped by the people within. This got me thinking about ‘place’ in terms of online education. Do students view an online class as a ‘place’? If they do, how can educators make an online space into a place for learning?

Place in context of human geography has two elements—the physical characteristics of the natural environment and the human influences—ideas, interactions and interventions. There are several books on the concept of place including “Place: A Short Introduction” by Tim Cresswell, author and professor of human geography. Cresswell describes place not only as a location, but as a physical space where humans produce and consume meaning (2004). “Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience” by Yi-Fu Tuan, one of the first scholars in the discipline of human geography, describes place and space as a relationship, that includes the feelings and thoughts humans associate with each (2001).

Why Online Students Need a Place

When examining face-to-face education settings we get a sense of how place influences learning. Inherent to education is the idea of going to a place to learn—a place to study, to meet with classmates, to lecture, to engage in discussion, to do research, etc. And a place’s physical aspects—the decor of a room, the temperature, WiFi availability, space constraints, available resources, even furniture, can influence students motivation, their effectiveness or even willingness to learning. As do the human aspects associated with a learning place—interactions, discussions, institutional processes, etc. In my experience it’s these human aspects that are most often associated with online education. Yet a sense of place that addresses the physical aspects in an online course is more elusive. Elusive—but necessary.

How Do Educators Make a Place Online

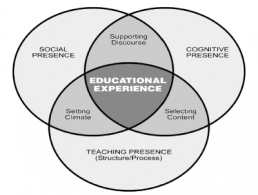

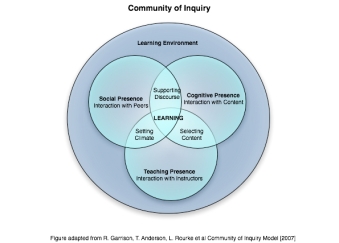

Few resources exist for educators wanting to learn about place-making in an online class. The closest I’ve found is the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model; a framework for describing presence online. The CoI model encompasses three dimensions of presence for online learning spaces: teaching, social and cognitive presence. The model suggests that effective education experiences occur when the three dimensions coincide. This is a good starting point for place-making. It addresses the human aspect of place-making through the three dimensions. Yet as mentioned, addressing the physical dimensions of place-making online is more challenging.

Example 1: Creating Dynamic Online Course Sites with Digital Tools

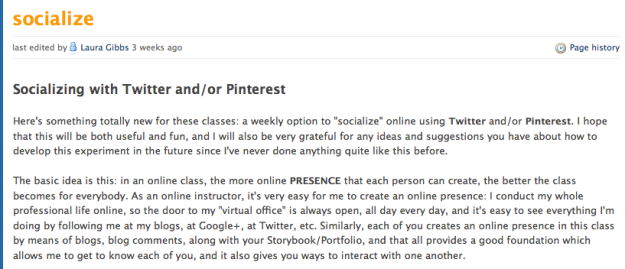

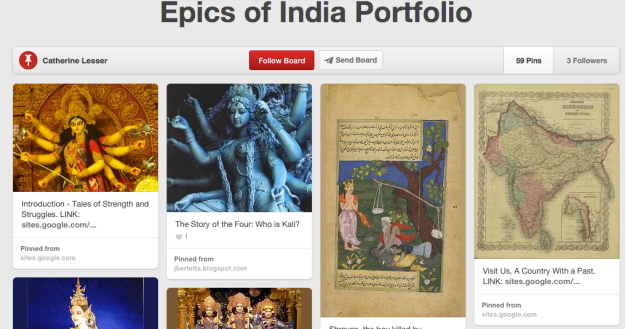

Effective use of Images and media can contribute to place-making. An experienced online educator Laura Gibbs (@onlinecrslady) maintains a dynamic course site for each of her online classes (Mythology and Folklore) using embedded images and content representing students’ course work from various digital platforms. Not only do students get to see their work featured on the course site, but the course becomes a dynamic space for learning. When students log-on to the course site, the most recent student assignment is featured (screenshot below), which students can access via an active link. Gibbs’ use of media tools (Rotate Content, inoreader widgets, etc.) and platforms (Twitter, Pinterest, Blogger) support place-making by creating a learning space that has meaning and purpose for students. Students shape the space by their contributions, interactions and involvement—making it a ‘place’ for their learning.

Screenshot of a web page in one of Gibbs’ online courses. This page features students completed writing assignment discussing Carol Dweck’s Growth Mindset that uses the Blogger platform. Visit this link to view Gibbs’ assignment instructions for students: http://onlinecourselady.pbworks.com/w/page/99035216/growthmindset

Using Twitter as a tool to contribute to place-making in an online course.

Screenshot of Tweet featured on one of Gibbs’ course sites. Gibbs posts Tweets featuring course updates, links to relevant resources; students also contribute.

Example 2: The Student Lounge

Some online courses feature a ‘student lounge‘, usually a discussion forum or chat room within the course site labeled as such. In my experience these lounges typically aren’t used, usually because there’s little invitation or reason to get involved—it’s just there. Yet there are ways instructors can make these spaces inviting and dynamic, to construct and lay the foundation for place-making. As we saw in the previous example, it takes a focused effort by the instructor to support place-making. Below are ideas for creating a student lounge from high school teacher Heather Wolpert-Gowan outlined in a blog post:

It is not hard to create a virtual student lounge in an online classroom. Think about what a student union provides and go from there. Make sure that students go there first, familiarize themselves with the space, and are encouraged to return to it time and again to recharge their social batteries. It should be a place where everyone can hang out and share, [by] posting, uploading and downloading. You can also create a “water cooler” thread that serves as just a fun way to build your community, introducing students to each other as members of a Virtual Learning Community (VLC.)…For instance, you might want to set up a space or thread that:

- Links to resources or even a gift shop of materials and supplies that students can buy or access in order to supplement their learning

- Allows students can share thoughts, writings, and videos

- Serves as an “information desk” so students can ask questions about the classroom and/or the content

- Acts as an “arcade” of links to content-related games and entertainment

- Promotes and celebrates learners in the community for their academic or personal accomplishments both online and offline

Closing Thoughts

The idea of ‘place’ in online education is an interesting one; it’s another way thinking about and approaching online education. The idea of place-making in online courses could be one way to engage and motivate students, to make learning relevant, meaningful and effective in our digital world. If you have ideas for place-making in online courses, readers would be interested—please share!

References

- Cresswell, T. (2004). Place: A short introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Robbins, P. (2014). The importance of place. Lecture presented in Understanding cultural and human geography. Chantilly, VA: The Great Courses.

- Tuan, Y. (2001). Space and place: The perspectives of experience. Minneapolis, MN. University of Minnesota Press.